The belief that ‘we eat with our eyes’ is only half the story; in reality, we taste with our entire brain, which is easily tricked by powerful sensory illusions.

- The color of your plate, the weight of your fork, and even the sound a food makes can dramatically alter its perceived flavor and value.

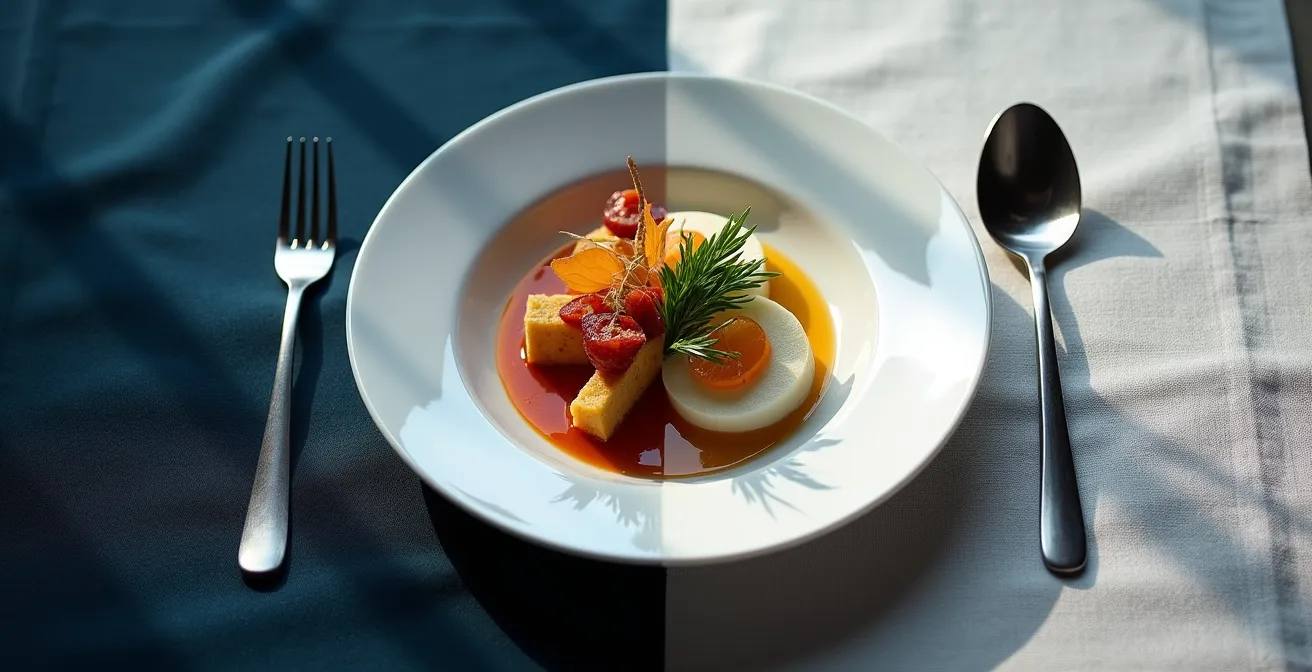

- Artistically arranged food doesn’t just look better—studies prove it scientifically tastes better by setting higher expectations in the brain.

Recommendation: Stop just cooking ingredients; start composing multisensory experiences to truly elevate your dining.

You’ve likely experienced it: a simple dish of seared scallops, something you’ve made at home, suddenly tastes revelatory in a fine-dining restaurant. The ingredients are the same, but the experience is transcendent. Why? The secret lies not just on the plate, but deep within the architecture of our brains. The classic wisdom suggests using round, white dishes because “it makes the food pop,” but this barely scratches the surface of a fascinating field known as gastrophysics. This is the science of how our environment and expectations shape our perception of flavor.

The truth is, our sense of taste is surprisingly suggestible. We don’t just taste with our tongues; we taste with our eyes, our hands, and our ears. This phenomenon, known as sensory transference, means we unconsciously transfer characteristics of the container to the food itself. For instance, research from Oxford University has shown that coffee can taste nearly twice as intense when drunk from a smooth, white ceramic mug compared to a clear, glass one. The brain is making a simple but powerful association: white and smooth equals more intense. The round white plate isn’t just a blank canvas; it’s the first step in a powerful psychological priming effect.

This article will deconstruct these “flavor illusions.” We will explore how simple changes in color, weight, and texture are not mere decoration, but powerful tools that act directly on the brain’s perception centers. By understanding these neurological triggers, you can move beyond following simple plating rules and start architecting a complete sensory experience that makes your food genuinely taste better, without changing a single ingredient in the recipe.

To guide you through this sensory journey, here is a breakdown of the key psychological levers you can pull to transform your culinary creations from simple meals into memorable experiences.

Summary: Why Food Tastes Better When Plated on Round White Dishes?

- How to Use Red and Yellow to Trigger Hunger Subconsciously?

- Heavy Silverware or Light Plastic: Which Increases Perceived Food Quality?

- The Texture Mistake That Makes a Dish Feel “Boring” to the Brain

- The “Instagram Effect”: How Visuals Are Changing Recipe Development?

- When to Serve the Heaviest Course in a 7-Course Meal?

- How to Match the Crunch of a Tostada With the Softness of Sashimi?

- When to Pair White Chocolate With Caviar for Molecular Harmony?

- How to Combine Mexican and Japanese Flavors Without Creating a Mess?

How to Use Red and Yellow to Trigger Hunger Subconsciously?

The power of color in food perception extends far beyond making a dish look “appetizing.” Colors act as a form of cognitive priming, sending powerful, instinctual signals to our brain that set expectations long before the first bite. Red and yellow are particularly potent in this regard. From an evolutionary perspective, these colors often signal ripeness, energy, and sweetness in fruits and other natural foods. Think of a ripe red strawberry or the golden hue of honey; our brains are hardwired to associate these colors with a rewarding, high-energy food source.

This deep-seated association is why the fast-food industry has built empires on red and yellow logos. These colors can subconsciously trigger feelings of hunger and excitement. When used in plating, they can make food seem more flavorful and satisfying. As a research team noted in The Shillong Times, our expectations are firmly set by color: “We expect red foods to be sweet, green foods to feel bitter or sour, and golden-crisp foods to crunch.” By placing a vibrant red coulis or a sprinkle of yellow saffron, you are not just adding color; you are sending a direct signal to the brain to anticipate sweetness and pleasure, effectively pre-programming a more positive taste experience.

This isn’t just theory; it’s a fundamental aspect of neurogastronomy. An incredible 50% of the brain is involved in visual processing, and leveraging these pre-existing color associations is one of the most direct ways to influence how a dish is ultimately perceived. A dab of red or a splash of yellow can be the difference between a dish that is merely eaten and one that is truly savored.

Therefore, when designing a plate, think like a psychologist. Use these powerful hues not as an afterthought, but as a strategic tool to guide your guest’s palate toward the exact experience you want to create.

Heavy Silverware or Light Plastic: Which Increases Perceived Food Quality?

The sensory experience of a meal begins the moment a guest picks up their fork. The weight, texture, and even the temperature of the cutlery trigger a powerful psychological phenomenon known as sensory transference. Our brains are not skilled at isolating sensory inputs; instead, we unconsciously transfer the properties of the object we are holding onto the food we are about to eat. Consequently, heavy, substantial silverware almost universally increases the perceived quality, value, and even flavor of a dish.

When you hold a utensil with significant heft, your brain makes a series of rapid, subconscious judgments: “This is substantial. This is high-quality. This is valuable.” These perceptions are then transferred directly to the food. The same yogurt, when eaten with a weighted spoon, is often rated as denser, creamier, and more expensive than when eaten with a flimsy, lightweight plastic spoon. The yogurt hasn’t changed, but your brain’s perception of it has been fundamentally altered by the tactile information from your hand.

This is why fine-dining restaurants invest in high-quality, heavy cutlery. It’s not merely about durability or tradition; it’s a calculated investment in the diner’s psychological experience. The feeling of quality begins in the hand, setting a precedent of luxury and care that elevates the entire meal. Light, cheap-feeling cutlery does the opposite, subtly communicating that the food may also be cheap or of lower quality, regardless of the chef’s actual skill.

As this comparison illustrates, the context provided by the tools we use is not trivial. The brain takes these physical cues as direct evidence of the food’s inherent worth. Choosing heavy silverware is one of the simplest and most effective ways to make a dish feel more luxurious and satisfying before it even touches the lips.

Ultimately, the choice of cutlery is not just a practical decision; it is an integral part of the flavor narrative you are creating for your guests.

The Texture Mistake That Makes a Dish Feel “Boring” to the Brain

The most common textural mistake in cooking is not a lack of texture, but a lack of textural *contrast*. A dish that is uniformly soft, crunchy, or smooth quickly leads to what neuroscientists call sensory-specific satiety. The brain, an organ that craves novelty, becomes bored. After a few bites, the signals of enjoyment diminish, and the dish starts to feel monotonous and uninteresting, no matter how good its flavor is.

Creating dynamic textural contrast is about building a sensory journey within each mouthful. The brain is stimulated by surprise and transition. A successful dish might start with a crisp element that gives way to something creamy, which is then punctuated by a soft, yielding component. This layering of textures keeps the brain engaged and prevents the palate from “tuning out.” The mistake is to serve a creamy soup with only a creamy garnish, or a crunchy salad with only other crunchy vegetables. This textural uniformity is the fastest way to make an otherwise delicious dish feel “boring.”

The ultimate expression of this principle goes beyond just food textures and incorporates auditory elements, a key part of the multisensory experience.

Case Study: Heston Blumenthal’s “Sound of the Sea”

At his legendary restaurant The Fat Duck, chef Heston Blumenthal serves a seafood dish called “Sound of the Sea.” It arrives with an iPod tucked into a large conch shell. Diners are instructed to put on the earbuds and listen to the sounds of crashing waves and seagulls as they eat. As confirmed by countless diners and studies, this auditory texture dramatically enhances the perception of freshness and saltiness in the seafood, demonstrating that what we hear is an integral part of what we taste.

To avoid the trap of textural monotony, you must think of your dish as a composition of contrasting sensations. The goal is to provide a dynamic experience in every bite, keeping the brain intrigued and engaged from start to finish.

This approach elevates a meal from simple sustenance to an interactive and memorable event.

The “Instagram Effect”: How Visuals Are Changing Recipe Development?

The rise of visually-driven social media platforms like Instagram has fundamentally altered our relationship with food, creating what can be called the “Instagram Effect.” This is not just about a fleeting trend of photographing meals; it’s a profound shift where the anticipated visual appeal of a dish begins to influence recipe development itself. Chefs and home cooks are increasingly asking not just “How will this taste?” but also “How will this look in a photograph?” This is because a dish’s visual artistry directly primes the brain for a better taste experience.

This isn’t just vanity; it’s proven gastrophysics. When we see a dish that is plated with clear intention and artistic flair—swooshes of sauce, precisely placed microgreens, a thoughtful arrangement of components—our brain’s expectation levels are raised. This heightened anticipation causes us to pay closer attention, search for more complex flavors, and ultimately, report a more positive taste experience. The food literally tastes better because we expect it to.

This psychological hack has tangible economic value. In one study, diners were presented with the same salad, plated in one instance as a simple pile and in another as a carefully constructed, artistic arrangement. The results were stark: an industry study of 60 participants showed that not only did more people prefer the artistic presentation, but they were also willing to pay significantly more for it.

Case Study: The Kandinsky-Inspired Salad

In a landmark gastrophysics study, gastrophysicist Charles Michel and his colleagues demonstrated this principle with scientific rigor. They created a salad with ingredients like scallops, mushrooms, and cauliflower purée. When the ingredients were simply placed on a plate, diners rated it as average. However, when the exact same ingredients were meticulously arranged to resemble the abstract painting ‘Painting No. 201′ by Wassily Kandinsky, the diners’ ratings skyrocketed. They found the Kandinsky-styled salad tasted significantly better and were willing to pay more for it, proving that artistry on the plate directly translates to perceived flavor and value.

The takeaway is clear: investing time in the visual composition of your dish is not frivolous. It is a direct investment in its flavor.

When to Serve the Heaviest Course in a 7-Course Meal?

Structuring a multi-course meal is akin to writing a story. It requires a narrative arc with a beginning, a rising action, a climax, and a dénouement. The placement of the heaviest course—typically the main protein or richest dish—is critical to the success of this narrative. Serving it too early can overwhelm the palate and lead to premature satiety, making subsequent courses feel like a chore. Serving it too late can be unsatisfying, as the diner may already be full or their sensory acuity diminished.

The optimal placement for the heaviest course in a seven-course meal is typically as the fifth course. Here’s the psychological reasoning: 1. Courses 1-2 (The Exposition): These are the amuse-bouche and a light appetizer (like a crudo or a clear soup). Their role is to awaken the palate and introduce the meal’s themes without causing fatigue. 2. Courses 3-4 (The Rising Action): These courses build in complexity and intensity. This might be a light pasta, a vegetable-forward dish, or a piece of seared fish. They build anticipation for the main event. 3. Course 5 (The Climax): This is the moment for the star of the show—the rich, complex, and most substantial dish (e.g., braised short rib, a rich cassoulet). The diner’s appetite and attention are at their peak, ready to appreciate the most impactful flavors. 4. Course 6 (The Falling Action): This is the cheese course or a pre-dessert. It serves as a bridge, cleansing the palate and transitioning from savory to sweet. It’s lighter and more contemplative. 5. Course 7 (The Resolution): The dessert. This provides a final, satisfying note to conclude the story.

Placing the heaviest dish at position five ensures it serves as the meal’s peak emotional and sensory experience. It satisfies the diner’s building hunger and provides the memorable centerpiece around which the other courses pivot. Deviating from this structure, for example by placing it at course three, rushes the climax and makes the rest of the meal feel like an epilogue.

By understanding this narrative flow, a chef can guide a diner through a journey that is satisfying, memorable, and well-paced.

How to Match the Crunch of a Tostada With the Softness of Sashimi?

Combining elements with extreme textural opposition, like the brittle crunch of a corn tostada and the yielding softness of high-grade sashimi, presents a significant challenge in fusion cuisine. When handled poorly, the result is textural dissonance—a jarring experience where the two textures fight each other rather than complementing one another. The brain struggles to process the conflicting signals, and the dish can feel disjointed or even unpleasant. The secret to success lies in creating a “texture bridge.”

A texture bridge is an intermediate ingredient that provides a gradual transition between two extremes. It acts as a buffer, mediating the sharp contrast and helping the brain perceive the combination as harmonious rather than chaotic. In the case of a tostada and sashimi, the bridge needs to have properties of both crunch and softness, or a lubricating quality that unites them.

For this specific Mexican-Japanese fusion, a creamy, fatty element is the perfect bridge. A layer of avocado cream or a spicy aioli serves this purpose beautifully. When you take a bite, your teeth first encounter the sharp crunch of the tostada, but almost immediately sink into the smooth, coating fat of the avocado. This creaminess then ushers in the delicate, cool softness of the sashimi. The avocado acts as a sensory mediator, slowing down the textural collision and blending the two opposing worlds into a single, cohesive bite.

Without this bridge, the experience is abrupt: a sharp, loud crunch followed by a silent, soft yielding. With the bridge, the experience becomes a seamless and satisfying progression. The following table outlines some common ingredients used to bridge textures in fusion dishes, based on principles highlighted in recent food science analyses.

| Bridge Ingredient | Texture Profile | Best Application |

|---|---|---|

| Avocado cream | Smooth, fatty, coating | Mexican-Japanese fusion |

| Aioli | Creamy, emulsified | Mediterranean-Asian fusion |

| Tobiko | Popping, moist | Adds intermediate crunch |

| Tempura batter | Light crispy coating | Protects delicate proteins |

By consciously building these bridges, you can turn a potentially jarring textural clash into a celebrated and harmonious contrast.

When to Pair White Chocolate With Caviar for Molecular Harmony?

The pairing of white chocolate and caviar is a classic example of a counter-intuitive combination that works brilliantly, defying traditional flavor logic. It’s a creation born not from centuries of culinary tradition, but from the modern field of molecular gastronomy. The success of this pairing hinges on the food pairing hypothesis, which posits that ingredients sharing key aromatic compounds will taste good together, even if they seem wildly different.

This pairing should be deployed when the goal is to create a moment of surprise, delight, and intellectual curiosity in a meal. It’s not an everyday combination but a showstopper, best used in an amuse-bouche or a composed appetizer where it can be the star. The key is understanding *why* it works: both white chocolate and caviar are rich in amines, a class of organic compounds. When tasted together, these shared molecules create a synergistic effect, amplifying savory, briny, and buttery notes in a way that neither ingredient could achieve alone. This creates a state of molecular harmony.

The context for serving such a pairing is crucial. It works best in a minimalist presentation where the focus is entirely on the two main ingredients. A small quenelle of white chocolate ganache topped with a dollop of high-quality caviar, perhaps with a hint of salt or a single herb leaf, is all that’s needed. Over-complicating the dish with other strong flavors would disrupt the delicate molecular conversation between the two protagonists.

Case Study: The Amine Synergy

Pioneering research into the molecular profiles of foods revealed the high concentration of amines in both white chocolate and caviar. This discovery, championed by chefs like Heston Blumenthal, led to the popularization of the pairing. It serves as a textbook example of how a scientific understanding of flavor compounds can unlock novel and surprisingly harmonious combinations that traditional, experience-based cooking might never discover.

Ultimately, this pairing should be used to create a memorable “flavor moment” that challenges a diner’s expectations and showcases a deeper understanding of the science of taste.

Key Takeaways

- Visual Priming is Real: The color, shape, and artistry of your plating set powerful expectations that scientifically alter the brain’s perception of taste.

- Taste is Transferred: The physical properties of your tableware, such as the weight of your cutlery, are unconsciously transferred to the food, changing its perceived quality and value.

- Compose a Sensory Story: The most memorable dishes offer a narrative of contrasting textures and sensations, preventing sensory boredom and keeping the brain engaged with every bite.

How to Combine Mexican and Japanese Flavors Without Creating a Mess?

Fusion cuisine, particularly the bold combination of Mexican and Japanese flavors, walks a fine line between innovation and confusion. A “fusion” dish that simply throws ingredients together—a jalapeño on a piece of sushi, for example—often results in a chaotic mess that respects neither culinary tradition. The key to successful fusion is not a random mixing of ingredients, but a structured and thoughtful integration of philosophies. A successful approach requires establishing a clear hierarchy within the dish.

The most effective method is the “Anchor and Accent” framework. This involves choosing one cuisine to serve as the “anchor” of the dish, providing its core structure, cooking method, and overall profile. This anchor cuisine should represent about 70-80% of the dish’s identity. The second cuisine is then used for “accents”—specific, targeted interventions like a sauce, a garnish, or a spice that introduces a surprising yet complementary note. For example, one could create a classic Japanese sashimi dish (the anchor) but serve it with a yuzu-and-serrano-chile vinaigrette (the Mexican accent).

This approach works because it provides the diner with a familiar foundation while still delivering the novelty and excitement of fusion. The goal is to find common ground. Both Mexican and Japanese cuisines, for instance, have a deep appreciation for umami (found in queso añejo and dashi, respectively) and a reliance on acidity for balance (lime and rice vinegar). By identifying and bridging these shared principles, a chef can create a dish that feels both innovative and strangely familiar.

Your Action Plan for Successful Fusion

- Establish the Foundation: Choose one cuisine as the ‘Anchor’ to provide approximately 70% of the dish’s structure and core flavor profile.

- Select Key Highlights: Use the second cuisine to provide specific ‘Accents,’ such as a unique sauce, a targeted garnish, or a finishing spice. Do not mix entire ingredient lists.

- Identify Shared Principles: Find the common ground between the two cuisines. For Mexican-Japanese, this could be a shared value for umami (e.g., queso añejo and dashi) or fresh seafood.

- Align Acidity and Balance: Match the acidity profiles to create harmony. The bright lime juice characteristic of Mexican food can complement the subtle, fermented acidity of Japanese rice vinegar.

- Layer Different Heat Types: Instead of clashing heats, layer them. For instance, pair the fruity, lingering heat of a Mexican chile with the sharp, pungent, and fleeting heat of wasabi.

The next time you are in the kitchen, remember you are not just a cook; you are an architect of experience. Start applying these principles today and watch as you transform simple meals into unforgettable sensory journeys.